ADIRE ELEKO : Starch resist

Cloths decorated by using starch made from cassava flour to resist the indigo dye were known as adire eleko. The starch was only applied to one side of the cloth so the underside would be plain blue. The use of starch allows for a greater variety in the patterns that can be created. Starch could be applied through a stencil or painted on to the cloth freehand.

Like

machine sewing, both cutting the stencil and using it were activities

performed by men. The starch was applied using a piece of metal; a

comb-like device could be used to create patterns in thickly applied

starch. The size and complexity of the stencils varied a great deal. One

of the most common stencilled designs features King George V and Queen

Mary at its centre. The image was originally taken from souvenirs

produced in 1935 to celebrate the silver jubilee.

Like

machine sewing, both cutting the stencil and using it were activities

performed by men. The starch was applied using a piece of metal; a

comb-like device could be used to create patterns in thickly applied

starch. The size and complexity of the stencils varied a great deal. One

of the most common stencilled designs features King George V and Queen

Mary at its centre. The image was originally taken from souvenirs

produced in 1935 to celebrate the silver jubilee.

Indigo

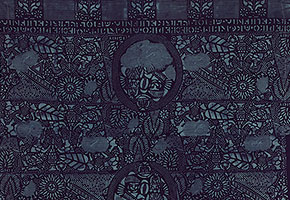

resist dyed cotton, Indigo resist dyed cotton, Ibadan, Nigeria 1960s

Museum no. Circ.590-1965. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

This is an example of adire eleko where starch has been applied through a metal stencil.

This is an example of adire eleko where starch has been applied through a metal stencil.

Detail

of indigo resist dyed cotton, Indigo resist dyed cotton, Ibadan,

Nigeria 1960s Museum no. Circ.590-1965. © Victoria and Albert Museum,

London

A detail from an adire eleko starch resist textile.

A detail from an adire eleko starch resist textile.

Hand painting was probably the most time consuming way of producing adire and these cloths were not subject to the same rapidly changing fashions as the adire oniko designs. The painting was done by women using chicken feathers, the mid rib of a palm leaf and matchsticks to create different thicknesses of line. Hand painted cloths were usually divided up into squares or rectangles which would then be filled in with a variety of patterns.

The centre of production for hand painted cloths was the city of Ibadan. The city itself was celebrated in one of the common patterns which was known as Ibadan dun, ‘Ibadan is good’ in Yoruba. This pattern takes its name from one square in particular which shows the pillars of Mapo Hall (Ibadan’s town hall) alternating with spoons. The example in the V&A collection also has Ibadan dun written on it, so there can be no doubt. Cloths, particularly hand painted ones, were often signed on the hem and this is one of two in the museum that has been signed using a symbol that appears to be a scorpion.

The symbol also appears on the front of the cloth in several places suggesting that having a cloth painted by this woman is something the owner would be keen for people to know. Unfortunately it has not been possible to associate the symbol with a name.

A gift in your will

You may not have thought of including a gift to a museum in your

will, but the V&A is a charity and legacies form an important source

of funding for our work. It is not just the great collectors and the

wealthy who leave legacies to the V&A. Legacies of all sizes, large

and small, make a real difference to what we can do and your support can

help ensure that future generations enjoy the V&A as much as you

have.

No comments:

Post a Comment